Sometimes, student days are commemorated after the fact, recalled from obscurity by later success or even philanthropy.

This was the case with the imperialist Cecil John Rhodes. He was Wilde and Cole’s contemporary at Oxford. He later endowed the Rhodes Scholarships.

Though a statue of this controversial alumnus now looks down on Oxford’s High Street, he was not especially influential within the University while a student. Often called away by business concerns, he had, by then, already discovered thousands of pounds worth of African diamonds and dreamed of controlling and unifying southern Africa. Although Wilde never mentioned Rhodes, it’s possible they met – both were members of the Oxford University freemasons and Rhodes was said to have attended Ruskin’s lectures.

Born in Hertfordshire, Rhodes entered Oriel College in 1873 and graduated in 1881. “I contend that we are the first race in the world,” he wrote in 1877, referring to the British, “and that the more of the world we inhabit the better it is for the human race … the absorption of the greater portion of the world under our rule simply means the end of all wars.” In the 1880s, his mining company, De Beers, was one of the largest in Africa and relied on exploitative, segregated labour. During his term as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890-1896, the 1892 Franchise and Ballot Act reduced voting rights for most Africans. A polarising figure in his own time as well as today, his will excludes women students from the scholarships but specifies that “race or religious opinions” should not disqualify a candidate. In 1977, women were finally allowed to apply for Rhodes Scholarships. Forty years later, Rhodes women discussed the changes they had witnessed in this video:

In 2020, Hera Jay Brown became the first trans woman elected as a Rhodes Scholar. Prof. Elizabeth Kiss, Warden of Rhodes House and CEO of the Rhodes Trust, acknowledged that “many elements of Rhodes’ original vision for the Scholarships were wrong and are obsolete. We reject his vision of educating young men to carry out a civilising mission, because of the imperialist, racist and sexist assumptions underlying its notion of civilisation. But the qualities sought in a Rhodes Scholar – intellectual distinction combined with concern for others, energy to lead, and a focus on public service – remain as compelling as they were over a century ago. … At the Rhodes Trust, our name and our history are a daily reminder of the moral obligation to engage with these issues and to affirm our human interconnectedness in its pain and its hope.”

In 2015, the Rhodes Must Fall protest movement began at the University of Cape Town in South Africa. Initially a campaign for the removal of a statue of Cecil Rhodes, it later developed into a movement to decolonise education at universities across the world. While a DPhil student in History at Pembroke College, Oxford, Brian Kwoba began work with co-editors Rose Chantiluke and Athi Nangamso Nkopo on a book that was published in 2018 as Rhodes Must Fall: The Struggle to Decolonise the Racist Heart of Empire. In the video below, Rhodes Scholar Hazim Hardeman, MPhil student at St John’s College, discusses what Locke’s achievement reveals about white institutions:

When Alain Locke’s mother counselled him not to apply for “that Rhodes thing”, he defied her, saying “I’m going to win that Rhodes Scholarship. It’s the least that Rhodes can do considering all the wealth he took from Africa.” An optimist in matters of race, Locke believed in “not looking for discrimination,” as he put it. He believed that if he behaved like he belonged, white people would believe he did. But this also meant regulating his own behaviour. At Harvard, he shunned other Black students, with the exception of the brilliant Antiguan James Harley (1873-1943), with whom Locke would soon coincide at Oxford, too. Both men shared a commitment to rivalling whites for the highest honours. Harley, one of the first students to study Anthropology at Oxford, later became a theologian and was elected to Leicestershire County Council.

Locke’s hopes of escaping American racism in Oxford were dashed when Rhodes Scholars from the American South singled him out for mistreatment. They were “mean-spirited enough to draw ‘the color line’” in England, and Locke found himself “suddenly shut out of things, – unhappy, and lonely,” one of his Jewish Oxford friends observed. Happily, Locke’s fortunes soon changed, and he found himself snowed under with invitations from students and faculty alike.

In an invited contribution to The Independent, Locke wrote that “the living conventions of Oxford social life are the fashions and customs of the English ‘public’ or preparatory schools.” Englishmen’s obsessions with class mirrored Americans’ fixation on race, he said. Oxford’s pose of neutrality in racial matters was repugnant to him, however. “Racially, I prefer a disfavour and… persecution even, to indifference. One cannot be neutral toward a class or social body without the gravest danger of losing one’s own humanity.”

In the video below, Rhodes Scholar Simone Askew reflects on her the high cost of being “the first”:

Simone Askew, Brigade Commander of the United States Corps of Cadets and Rhodes Scholar at Magdalen College

Cole, Wilde and Locke were well-versed in contemporary prejudice, race science and imperialist rationalizations for the exploitation of colonised peoples.

As a student at Oxford, Wilde read cutting-edge evolutionary science and greatly admired the writings of Herbert Spencer. He remained a lifelong student of Victorian race science, discussing it in essays including “The Soul of Man Under Socialism,” “The Critic as Artist” and “The Rise of Historical Criticism.”

In his writings, Cole rejected outright any “science” corroborating racial hierarchies and colonial paternalism. When an Oxford contemporary attacked “enlightened Negroes” in print, Cole retorted with a publication of his own in which he shrugged off the assault in no fewer than four languages. He approvingly cited Oxford alumnus Reginald Bosworth Smith’s 1874 lectures on Islam at London’s Royal Institution as a welcome example of “a man whose intellectual mould is of rare cosmopolitan adaptation” because he hoped that Blacks would resist European “civilisation” by force.

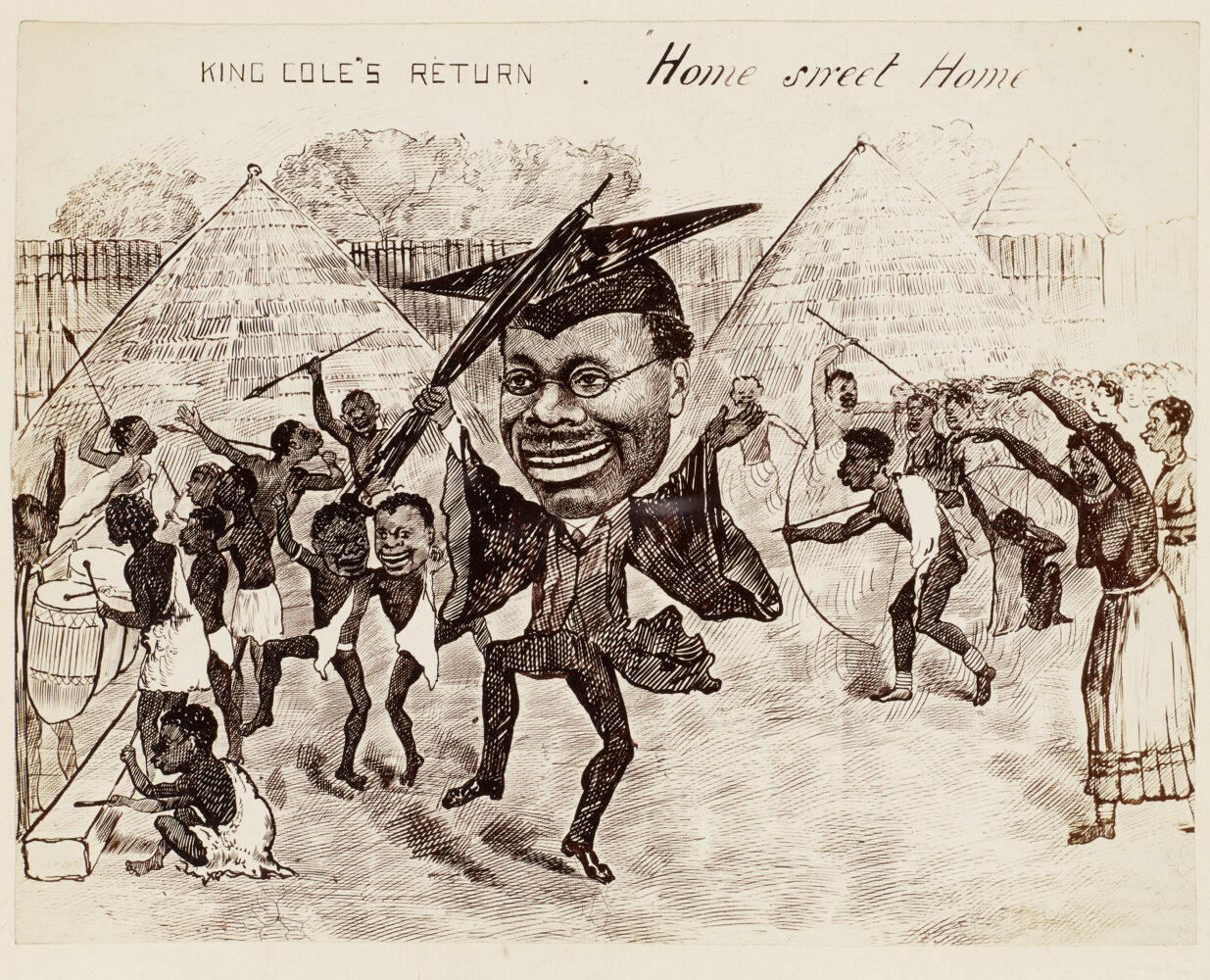

Cole’s signature in a borrowing register from Univ College Library, noting that he borrowed The Life and Letters of Lord MacCaulay. In the same year he also signed out Pater’s Studies in the History of the Renaissance. Univ Library borrowing book; Trevelyan’s Life and Letters of Lord Macaulay (1st ed., 1876). Courtesy of the Master and Fellows of University College Oxford: Univ Archive, UC:L1/A1/3 and Univ Library MVQ/MAC,T.

Cole’s library records show that he borrowed Trevelyan’s Life and Letters of Lord Macaulay, a bestselling biography of the British imperialist, politician, and advocate of English education for Indian students. You can see Cole’s big swirling signature from the University College Library borrowing book above.

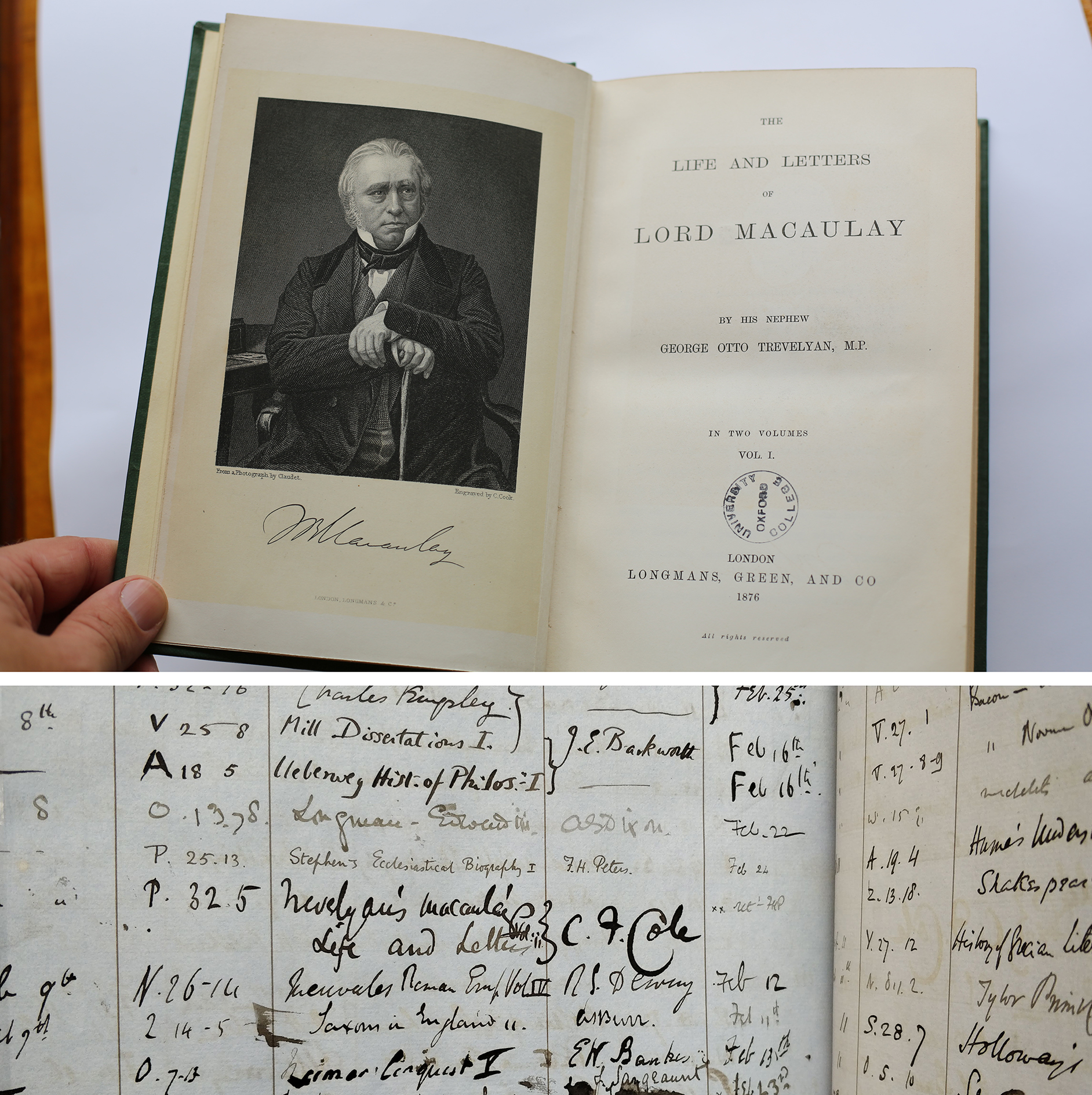

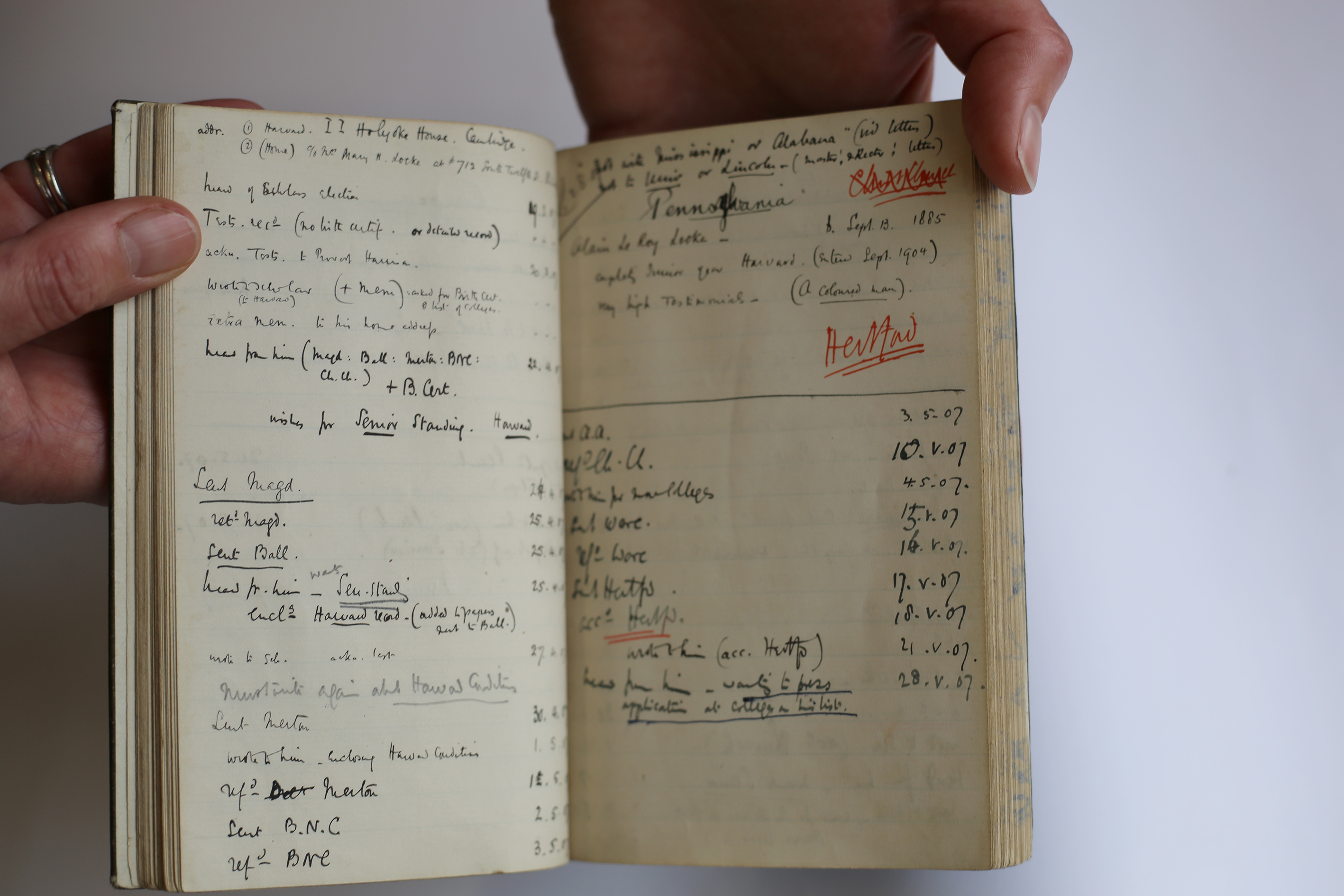

Notebooks kept by Sir Francis Wylie, first Warden of Rhodes House. In the first notebook, Wylie records the process of finding a College for Alain Locke, specifically ruling out University and Lincoln College because of racial tensions. The second notebook records Locke’s academic progress and later biographical details.

Sir Francis Wylie: Applications to Colleges, 1907; Warden’s Biographical Details, 1907.

By kind permission of the Trustees and Warden of the Rhodes Trust.

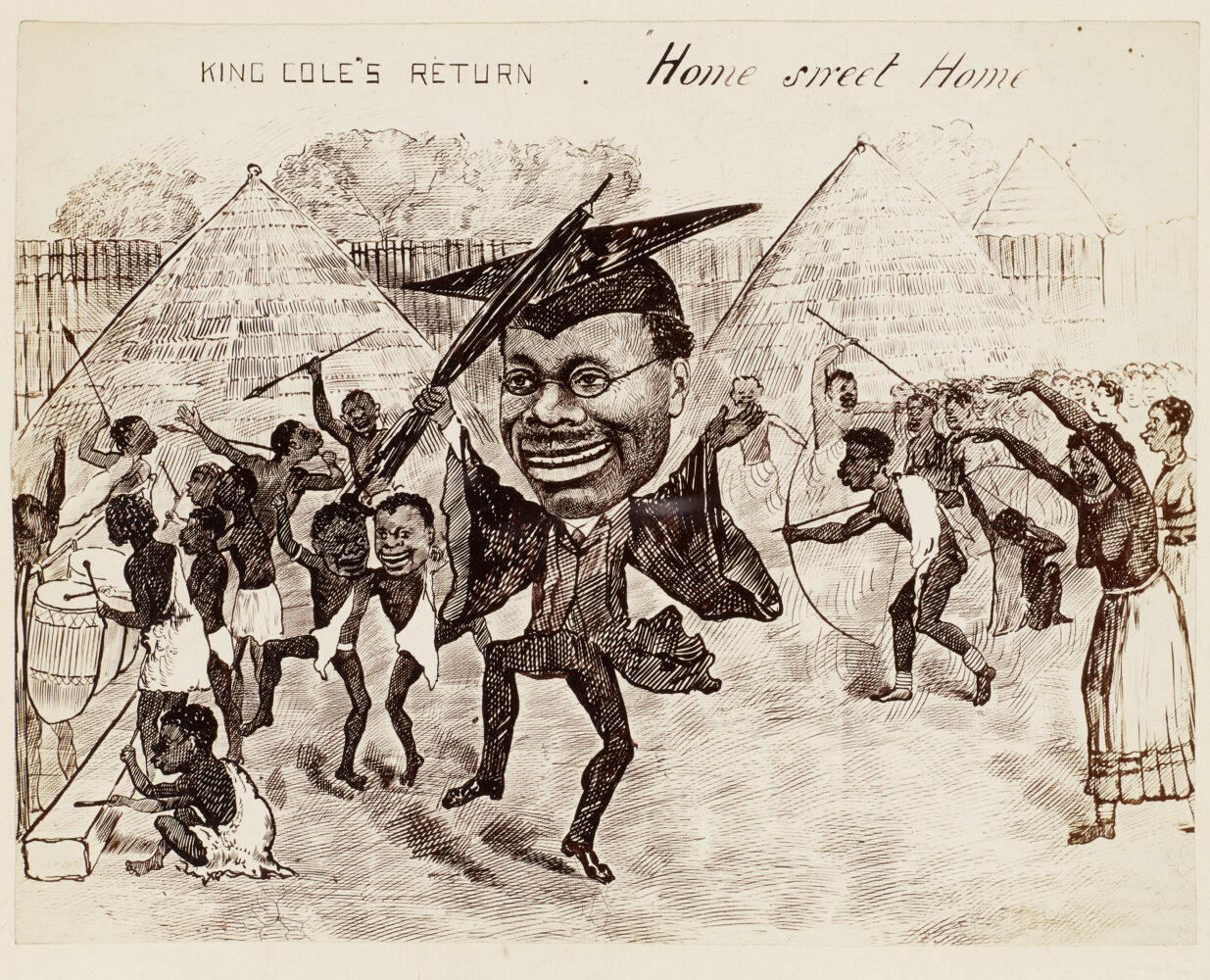

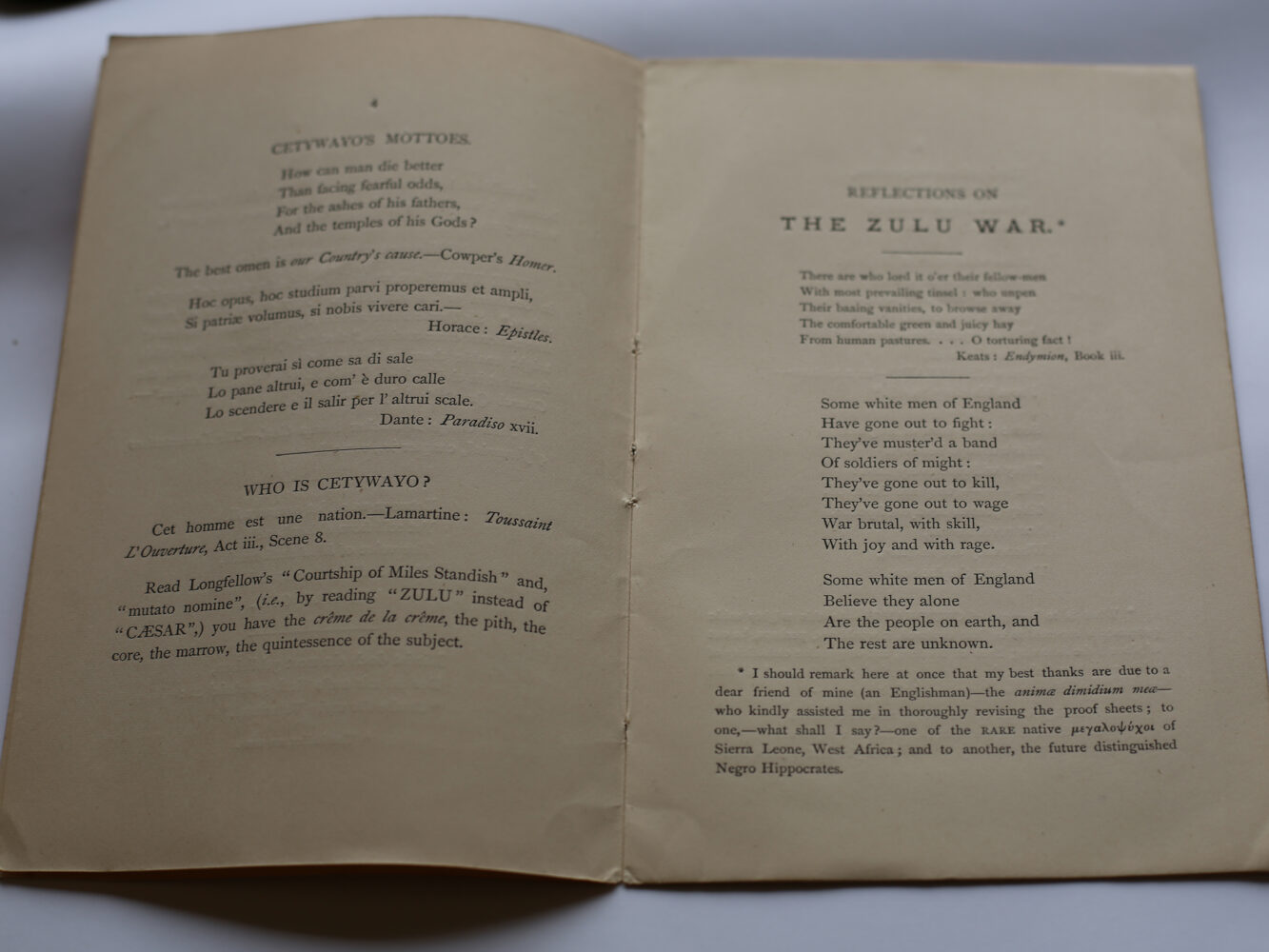

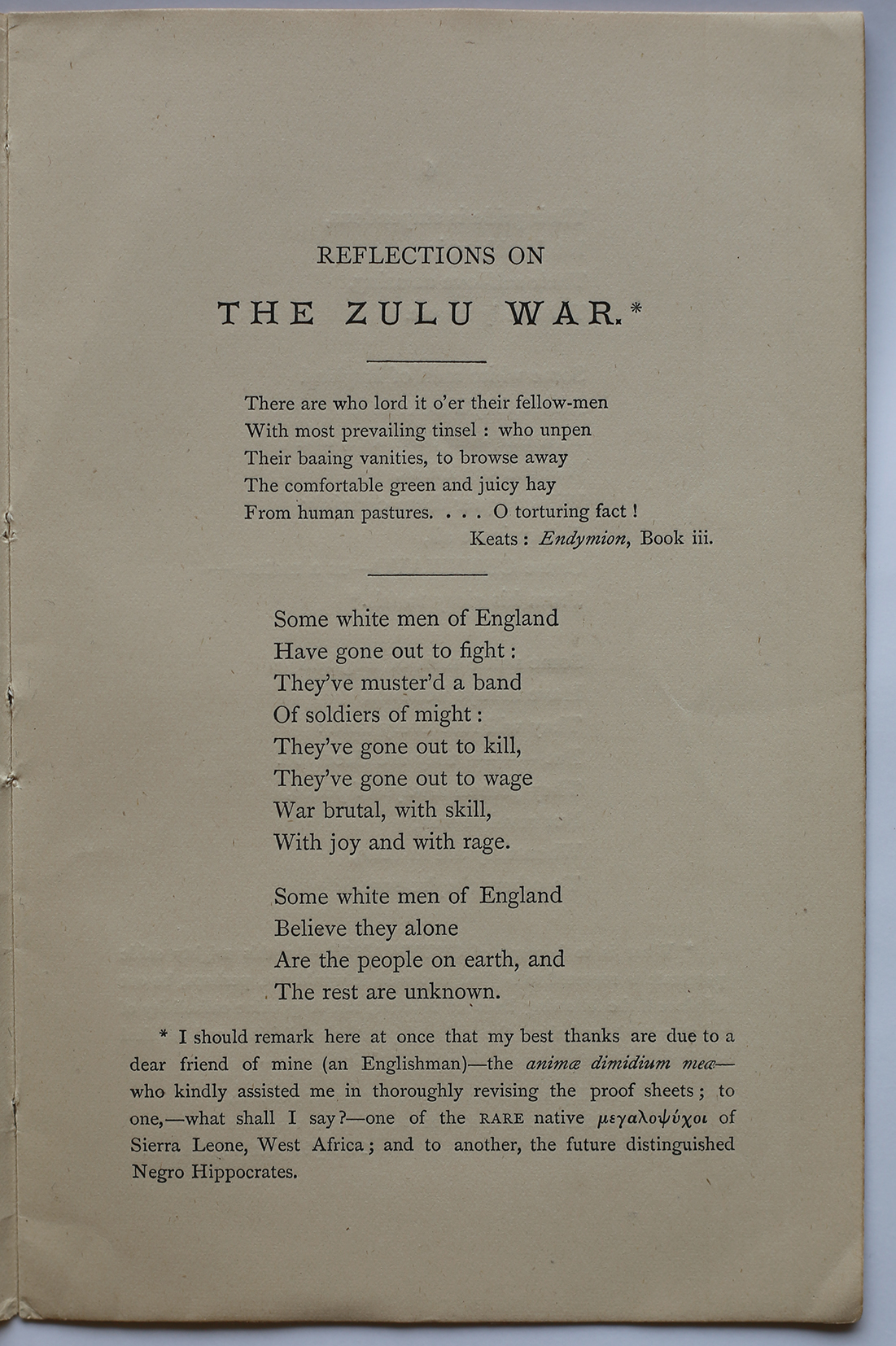

Cole made no secret of his contempt for the colonial mindset. How he smarted at his mistreatment in Oxford became apparent in 1879 when he published two pamphlets, What Do Men Say about Negroes? and Reflections on the Zulu War by a Negro, B.A. These exceedingly rare publications reveal his thoughts on contemporary international politics.

C. Cole, Reflections on the Zulu War by a Negro, B.A. (London: Glaisher, 1879): University College, KCL/COL.

Courtesy of the Master and Fellows of University College Oxford.

In 1879, Britain consolidated its imperial holdings in Africa as part of its Confederation policy. British forces invaded Zululand – an independent southern African realm half the size of Ireland – and the Oxford and Cambridge Undergraduate’s Journal portrayed Wilde as “O’Flighty” sending the “barbaric” Zulu King Cetshwayo KaMpande two gifts. The first was a few lines of O’Flighty’s poetry (quoted directly from Wilde’s poem “Ravenna”). The second gift was a case of eau de cologne and a polite request to ensure his men “are properly scented before going into action.” Three years later, when the real King of Zululand came to visit Queen Victoria and Prime Minister Gladstone, he was appalled at British behaviour. “I do not care to be made a show of,” King Cetshwayo KaMpande said of the massive audiences who came to stare. “If English people have never seen a black man before I am sorry. I am not a wild beast, I did not come here to be looked at.”

Cole’s Reflections on the Zulu War criticized British imperialism and spat at Christian “charity” towards so-called “heathens.”

Ye white men of England

Oh tell, tell, I pray,

If the curse of your land,

Is not, day after day,

To increase your possessions

With reckless delight,

To subdue many nations,

And show them your might.

In apocalyptic tones, he warned that whites would not always have the upper hand in Africa. “Some white men of England,” Cole wrote, “have always believed they will rule every land: but – they are deceived. They preach always of peace, but revel in war.”

Cole addressed the pamphlet from one of London’s Inns of Court, the Inner Temple, which had given him the right to practice, so making him Britain’s first Black African barrister.

“The Age of Darwin,” the ethnologist Bernth Lindfors observes, “was a century of aggressive imperialism compounded by great biological confusion.” In nineteenth century Britain, the term “African” often extended to include almost anyone with dark skin. The origins of the Irish Question and the Celtophobia that preoccupied the British throughout the nineteenth century stretched back to the eighteenth century.

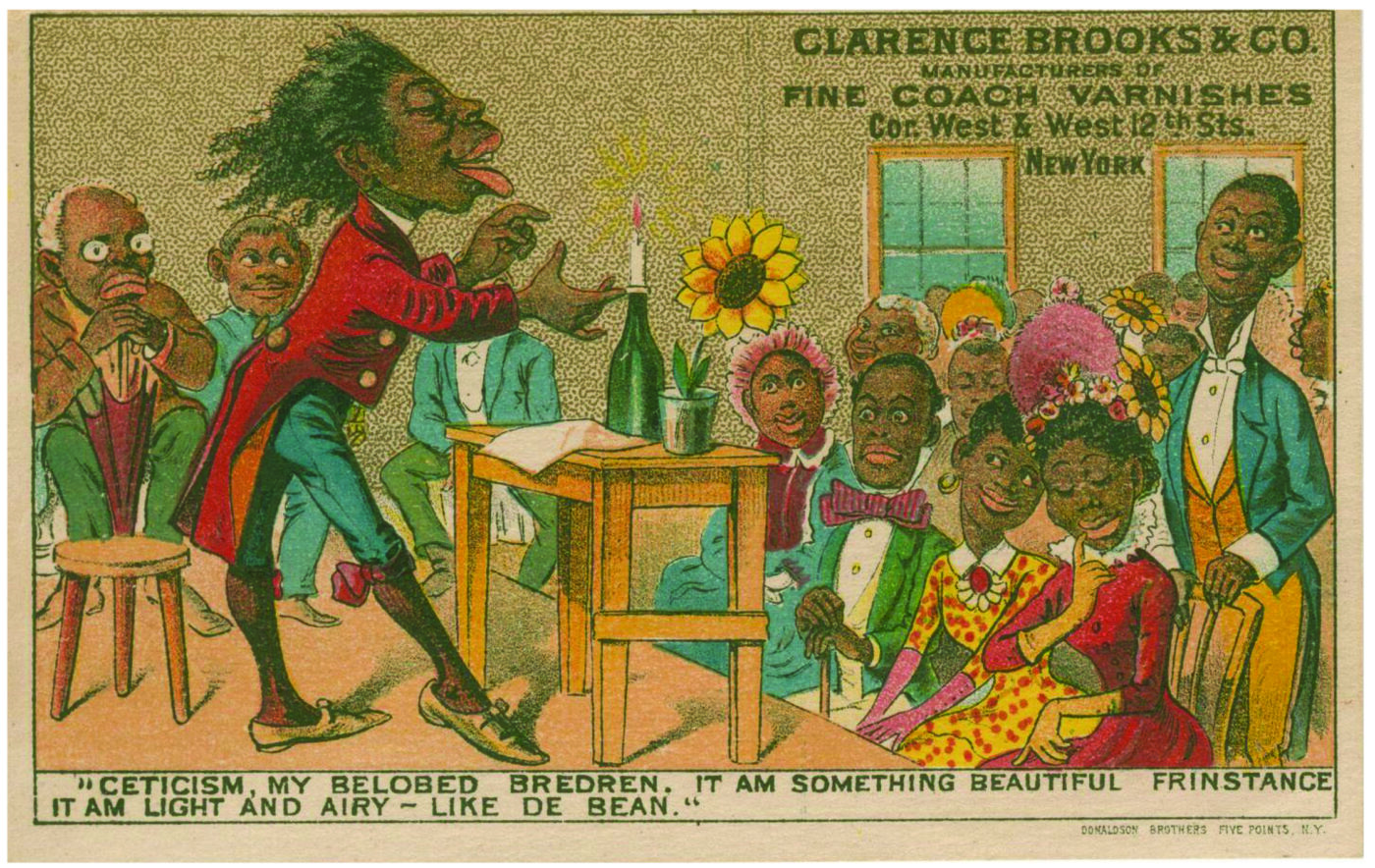

Depictions of people of colour and ethnic minorities were a staple of nineteenth century minstrelsy, a racist form of blackface entertainment said to have originated in the United States. First introduced into Britain in the late 1830s, blackface minstrelsy later became associated with “Christy minstrelsy”. The mid-nineteenth century pinnacle of minstrelsy’s popularity intersected with the rise of new racial “science” and ideologies that emphasized Black and Irish inferiority. By the century’s last decades, Negrophobia and Celtophobia were as joined as the proverbial horse and carriage.

Almost two decades before Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859, in the United States and Britain, popular performances were already playing on ideas of evolution. Between 1850 until the early 1880s, Christy minstrelsy was the premier entertainment on both sides of the Atlantic. Its mix of theatre, dance, and music became the go-to entertainment for everyone from working class men to well-to-do ladies and children. Many of the leading performers were Irish-Americans.

Wilde’s own distorted Irish image intersected with these blackface caricatures, as you can see from the images reproduced here. When he visited the United States in 1882, he was subjected to anti-Irish satires that continued to dog him at the height of his success in the 1890s.

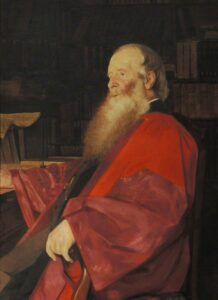

“Edward Augustus Freeman, Regius Professor of Modern History” oil on canvas by Hubert Vos (1889). Reproduced by kind permission of the President and Fellows of Trinity College, Oxford.

Shortly after Wilde and Cole graduated, the Oxford historian Edward A. Freeman (1823-1892), a fellow of Trinity College, toured the United States in 1881-1882 expounding his racist theories correlating “the Irish difficulty” in Britain to “the negro difficulty” in America.

As for Victorian Oxford’s most famous Irish undergraduate, Freeman said he had never heard of Oscar Wilde until he saw his name spelled out “in large letters on the walls, as his photographs, and various attitudes, were to be seen in the windows, at Washington and at several other places” throughout the United States, when Wilde lectured there in 1882-1883. It was only by travelling thousands of miles that the Trinity College don eventually discovered the young Irish aesthete whose Magdalen College rooms had once been less than a mile away from his own.

Freeman’s revolting racist notions did not even have the merit of originality. By then, linking together fears about the Irish and Blacks was already a longstanding practice among so-called advanced thinkers. His virulence had been anticipated by others such as Sidney and Beatrice Webb (“we detest [the Irish], as we should the Hottentots”), Thomas Carlyle (who believed that the solution to the “Irish Question” was to “black-lead them and put them over with the niggers”), and Charles Kingsley (who returned from Ireland “haunted by the human chimpanzees I saw along the hundred miles of that horrible country”).